Table of Contents

DHT-22 Air Temperature and Humidity Sensor

1. About the Sensor Module

Even though the DHT-22 is a sensor used to determine air temperature and relative humidity, what it actually measures are resistances and capacitances which are affected by temperature and humidity of the air, respectively. The DHT-22 combines two different sensors and a little circuit board in one device. The circuit board does calculations and also converts the analog output from the sensors to a digital output signal which can be read from the DHT-22 Data-pin using, for example, the Adafruit DHT sensor library.

In the monitoring station, the DHT-22 will be used to keep track of the air temperature and relative humidity at the pond bank. The collected data will then be transmitted using WiFi to an MQTT Broker.

1.1 Measurement of the Temperature

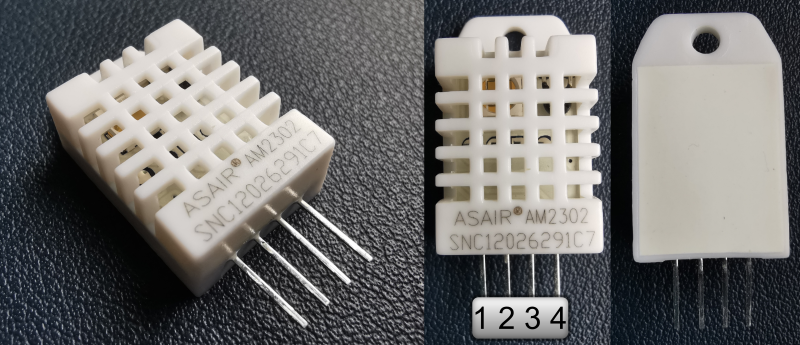

The first sensor is the temperature sensor which mainly consists of a thermistor, a thermally sensitive resistor. In figure 1, the thermistor is visible in the middle photo underneath the grid of the white casing in the top right. There are two different types of thermistors: NTC thermistors (NTC- Negative Temperature Coefficient) conduct electricity better the higher the temperature, that means their resistance decreases with increasing temperature, typically at a rate of 3 to 6% per °K. The second type of thermistors are PTC thermistors (PTC – Positive Temperature Gradient) whose resistance increases with increasing temperature. Both types can be used in different applications, for example to prevent peak currents, or limit the current during continuous operation. Because the change in resistance due a change in temperature is predictable and reproducible, they are well suited for measuring the temperature.

1.2 Measurement of the Humidity

The second sensor is the capacitive humidity sensor which is used for determining the relative humidity of the air. The sensor consists of a capacitor which uses the air between the contacts as a dielectric. The dielectric of a capacitor isolates the cathode and the anode from each other. The capacitance of the capacitor with vacuum as a dielectric is denoted as $C_0$. The dielectric constant $\kappa$ of a material is the ratio of the capacitance $C$ with the material as dielectric to $C_0$, so $\kappa=C/C_0$ or the ratio of the Electric field strength between anode and cathode in vacuum to the electric field strength with the dielectric $\kappa=E_0/E$. That means for vacuum $\kappa$ equals 1, and the dielectric constant for any material is greater than that. For dry air, the dielectric constant equals 1.00059, which is close to vacuum, so the capacitance is almost the same as in vacuum when the air is dry. For water, the dielectric constant equals approximately 80. With increasing moisture, the dielectric constant of the air increases, which also increases the capacitance of the capacitor. When the sensor is calibrated correctly, it is possible to assign a certain value for the actual vapor density of the air to a certain value of the capacitance. The relative humidity is the ratio of the actual vapor density to the saturation vapor density in percent. The saturation vapor density increases exponentially with increasing temperature. To calculate the relative humidity, it is thus necessary to also measure the temperature to obtain the current saturation vapor density of the air. In the DHT-22, temperature compensation technology is applied to account for the change in saturation vapor density due to temperature changes to give as accurate results for the relative humidity as possible.

2. Data Transmission

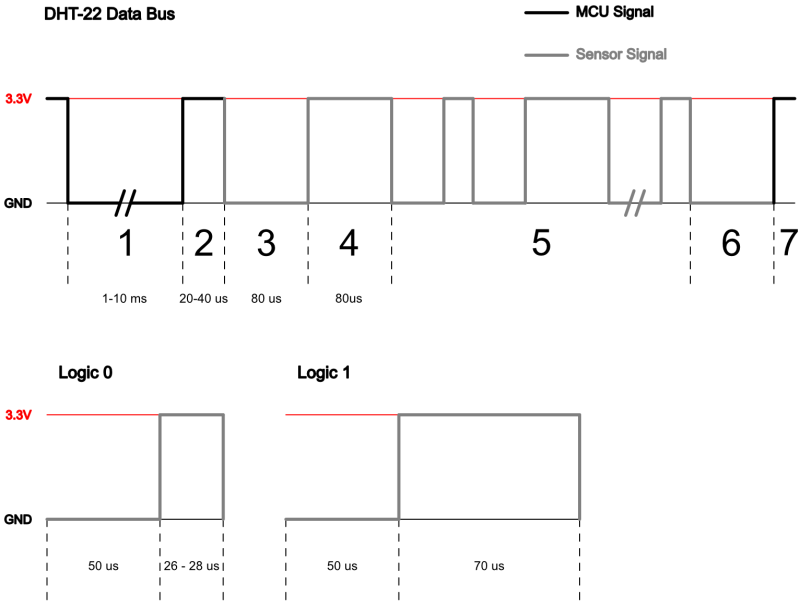

The communication between the DHT-22 and the microcontroller (MCU) occurs only via the 1-Wire data-bus connecting an MCU-pin and the Data-pin (Pin 2 in figure 1) of the DHT-22. The 1-Wire bus for the DHT-22 is specifically designed for DHT-xx sensors and is not compatible with the Dallas 1-wire bus used for the DS18B20 temperature sensors. In fact, the data-bus allows only the connection of 1 DHT-22 with an MCU. This is the case because, in this system, the sensors do not have individual addresses, like in the Dallas 1-Wire data-bus or in an I²C-bus. Connecting multiple DHT sensors with one data-bus, will result in all the sensors sending and occupying the only available connection at once, making data transmission impossible. The communication follows a fixed protocol which can be seen in figure 2 below:

2.1 Communication Protocol

During the seven steps, indicated in figure 2, the following happens:

- If the DHT-22 is ready to receive commands, the voltage level of the data-bus is high. When the MCU requests temperature and humidity, it pulls the data-bus to GND, which is the starting signal for communication between sensor and MCU. The signal is kept low for at least 1 – 10ms, to make sure that the DHT-22 detects the signal.

- Afterwards the MCU pulls the voltage level high for 20 – 40 us while waiting for the response of the DHT-22.

- If the DHT-22 has detected the signal, it will send a response signal by pulling the data-bus low for 80 us.

- Then it pulls the data-bus to a high voltage level for another 80 us while measuring the temperature and humidity and preparing the transmission of data.

- During this phase, the actual data are transmitted bitwise. Both, a logical 1 and a logical 0, start with a 50 us low signal. The duration of the following high signal determines whether it is to be interpreted as a 1 or a 0. If it is a 0, the signal is pulled high for 26 – 28 us, and if it is a 1, it is pulled high for 80 us. The duration of the complete transmission differs depending on the values that are transmitted. A signal consisting mostly of logical 1s, will need more time than one mainly consisting of 0s.

- When all 40 bits are transmitted, the sensor will pull the signal to low voltage level. The transmitted data can then be read by the MCU using the DHT library.

- To end the transmission, the MCU then pulls the data-bus to a high logical level again. The DHT-22 goes into stand-by mode until it receives another starting signal.

2.2 Data Transfer

As mentioned before, the data that is transmitted consists of 40 bits. 2 bytes for the relative humidity, 2 bytes for the temperature and 1 byte (check-sum) to check for finding errors in the transmission. The principle becomes clearer when looking at an example transmission:

$\mathrm{0000\; 0010\; 1000\; 1100\;\; 0000\; 0001\; 0101\; 1111\;\; 1110\; 1110}$

Humidity (1) | Temperature (2) | Check-sum (3)

-

Humidity

The first two bytes contain the relative humidity data, converted to decimal, that gives:

\[\mathrm{0000\; 0010\;\; 1000\; 1100_{2}} → 652_{10}\] To obtain the relative humidity RH in percent, the value must be divided by 10:

\[RH = \frac{\mathrm{652}}{\mathrm{10}} = \mathrm{65.2\;\%}\] -

Temperature

For the temperature it works in a similar way. The binary gets converted to decimal and is divided by 10 to obtain the temperature in °C:

\[\mathrm{0000\; 0001\;\; 0101\; 1111_2 → 351_{10}}\] \[T = \mathrm{\frac{351}{10} = 35.1 °C}\] Unlike relative humidity, the temperature can be below 0 (negative). If that is the case, the first digit of the first temperature byte (byte 3) is a 1. -

Check-sum

The last byte contains the 8 least significant bits (LSB) of the sum of both humidity and both temperature bytes:

\[\mathrm{0000\; 0010 + 1000\; 1100 + 0000\; 0001 + 0101\; 1111 = 1110\; 1110}\] After receiving the data, if the last byte (check-sum) is different from the 8 LSBs of the sum of the other 4 bytes, there was an error in the transmission. The MCU can thus check if the data was transmitted correctly.

3. Technical Specifications and Setup of the Sensor

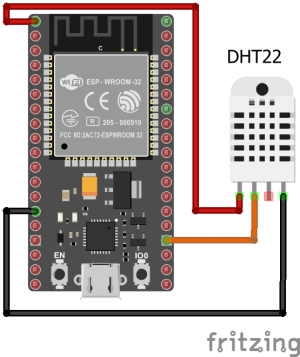

The DHT-22 comes with 4 pins and can be plugged into a breadboard. Pin 1 (VDD) is connected to the power supply, pin 2 (DATA) is the 1-wire data-bus and is connected to GPIO 15, pin 3 (NC) is not connected, and pin 4 (GND) is connected to 0 Volts (figure 3). Information on the technical specifications can be found in table 1.

| Table 1 Technical specifications, sensor accuracy and ranges | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model | AM3202 | |

| Power Supply | 3.3 - 5.5 V DC | |

| Current (3.3V) | Measuring: 1mA | Stand-by: 50μA |

| Power Consumption (3.3V) | Measuring: 3.3 mW | Stand-by: 0.165mW |

| Output signal | Digital signal using a 1-wire bus | |

| Sensing element | Polymer humidity capacitor | Thermistor |

| Operating range | 0 - 100 % RH | -40 - 80 °C |

| Accuracy | $\pm$ 2 % RH | $\pm$ 0.5 °C |

| Resolution/sensitivity | 0.1 % RH | 0.1 °C |

| Repeatability | $\pm$ 1 % RH | $\pm$ 0.2 °C |

The specifications are also available in the AM2302 Datasheet.

3.1 Pullup Resistors

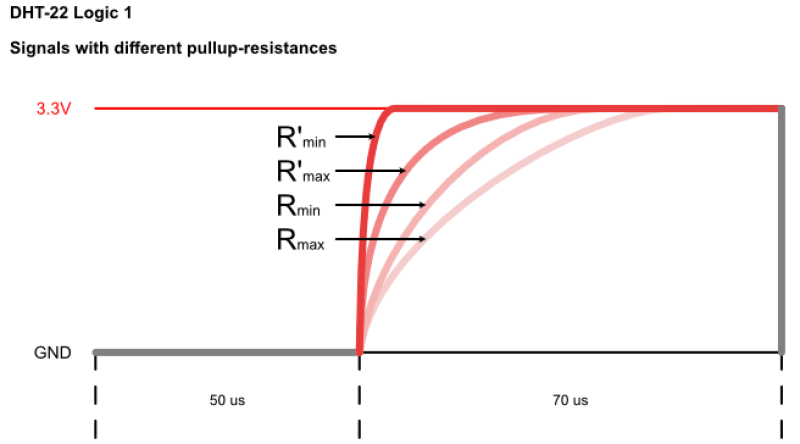

The data-bus is pulled to high potential using a 4.7kΩ pullup resistor connecting the data-bus and the VDD pin. The pullup resistor is already included in the DHT-22 sensor module. So, the module already works when the sensor is just connected like described above. Furthermore, the ESP32, just like the Arduino, has built-in pullup and pulldown resistors. The values for the pullup resistors vary from module to module and from pin to pin but are typically in the range of 30 – 80 kΩ. When creating an object from the DHT.h-library that represents the DHT-22, the number of the GPIO pin is given as an argument. To start the sensor, the method begin() is executed; this function configures the pin as an input and activates the ESP32’s internal pullup resistor for that pin. So, in reality, two pullup resistors, one from the DHT-22 and one from the ESP32 are used. The total pullup-resistance between the data-bus and VDD can thus vary between:

$$R_{min}=\left(\frac{1}{30000\Omega}+\frac{1}{4700\Omega}\right)^{-1}=4063.4\Omega$$ and $$R_{max}=\left(\frac{1}{80000\Omega}+\frac{1}{4700\Omega}\right)^{-1}=4439.2\Omega$$

When the sensor data pin and the GPIO of the ESP32 are connected through a longer cable (>50cm), it is advisable to use another external pullup-resistor. This is due to the fact that the wire acts as a capacitor, and the longer the wire is, the larger the capacitance. After a 0V pulse, the wire-capacitor has to be charged again before the data-bus reaches the full 3.3V potential. That means, instead of having a clean pronounced voltage signal, which can be interpreted as a 0 or 1, the signal looks like the charging curve of a capacitor (see figure 4). The longer the cable, the larger the capacitance resulting in a longer charging time and a less pronounced signal, which may lead to errors in the communication. Adding another external pullup resistor, for example a 10kΩ resistor, decreases the total pullup-resistance, because the resistors are connected in parallel. The new minimum and maximum resistances are thus:

$$R'_{min}=\left(\frac{1}{30000\Omega}+\frac{1}{4700\Omega}+\frac{1}{10000\Omega}\right)^{-1}=2889.3\Omega$$ and $$R'_{max}=\left(\frac{1}{80000\Omega}+\frac{1}{4700\Omega}+\frac{1}{10000\Omega}\right)^{-1}=3074.4\Omega$$

As the total pullup resistance decreases, the current increases and the wire-capacitor is charged faster (that means 3.3V on the data-bus is reached faster as well), which steepens the charging curve of the capacitor and thus makes the signal more “square”, so it is more pronounced and leads to less errors during communication between MCU and DHT-22. This effect is demonstrated in figure 4 and also occurs for other wire-connected bus-systems like I²C.

3.2 Other Issues and Problems that occurred

During the setup and testing of the DHT-22, some issues to be considered are:

3.2.1 Instable Phase

After supplying power to the DHT-22, the sensor has an unstable status, which requires the user to wait for one second until further commands can be sent.

3.2.2 Sampling Rate

As the sensor consumes more power during measurements, it is prone to heating up and thus influencing the measured temperature. To ensure that the measurements are not adulterated by the sensor heating up, it is required to keep the sampling rate at a maximum of 0.5 Hz, so 1 measurement every 2 seconds.

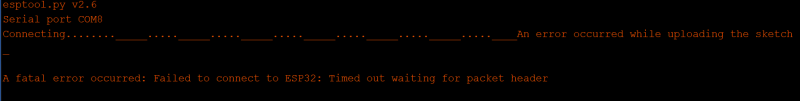

3.2.3 Upload-issues using the ESP32 DevkitC VB

When using the ESP32 instead of an Arduino, the Arduino IDE can give a time out error (figure 5) during the upload if the DHT-22 is already connected to the ESP32:

|

|---|

| Figure 5 Time out error during upload of code to the ESP32 DevkitC VB with the DHT-22 connected to it. |

This seems to be an issue caused by the power supply to the DHT-22 during the upload process. Other users reported to have fixed the problem by

- pressing and holding down the “Boot”-button on the ESP32 board when the computer tries to connect with the ESP32.

- using an additional power supply and connecting a 3.3V voltage source to the Vin pin of the ESP32.

However, in our experiments, the only approach that worked was to

- either remove the DHT-22 completely from the breadboard during upload, or

- only disconnect the voltage supply from the DHT-22’s VDD pin.

4. Programming the DHT-22

In this sketch the DHT-sensor-library from Adafruit was used to communicate with the DHT-22 and obtain the measurement results.

The following code is only part of the complete code that was uploaded to the ESP32 later on. The aim of this code was to test the DHT-22 with the ESP32 and create a function, that can later be easily implemented into the final code. It contains the function (measureDHTTemHum()) to be implemented later, the necessary variables, definitions and libraries. When the ESP32 with this code is connected to the computer via USB, it measures the temperature and humidity in 2 second intervals, averages the measurements to get more accurate results and prints it to the Arduino IDE's serial monitor.

4.1 Code

- ESP32_DHT-22_Test.ino

//DHT 22 Temperature and Relative Humidity Reading Function //Definitions #define DHTTYPE DHT22 //1 const int DHTPIN = 15; //2 //Libraries & Objects #include <DHT.h> //3 DHT dht(DHTPIN, DHTTYPE); //4 //Variable Declaration/Initialization float dht22AirTem = 0; //5 float dht22AirTemSum = 0; String dht22Temperature = ""; float dht22RelHum = 0; float dht22RelHumSum = 0; String dht22Humidity = ""; void setup() { delay(5000); //6 Serial.begin(115200); //7 Serial.println("Measurement is starting ..."); } void loop() { Serial.println("Measuring ..."); measureDHTTemHum(5); //8 Serial.println("Temperature: " + dht22Temperature + " °C"); //9 Serial.println("Relative Humidity: " + dht22Humidity + " %"); Serial.println("=============================="); delay(2000); //10 } void measureDHTTemHum (byte AveragingNumber) //11 { delay(1000); //12 dht.begin(); //13 dht22AirTemSum = 0; //14 dht22RelHumSum = 0; dht22Temperature = ""; dht22Humidity = ""; for (byte i = 0; i < AveragingNumber; i++) //15 { do { //16 dht22AirTem = dht.readTemperature(); //17 dht22RelHum = dht.readHumidity(); if (!isnan(dht22AirTem) && !isnan(dht22RelHum)) //18 { dht22AirTemSum += dht22AirTem; //19 dht22RelHumSum += dht22RelHum; } else delay(2000); //20 } while (isnan(dht22AirTem) || isnan(dht22RelHum)); //21 if (i < (AveragingNumber - 1)) //22 delay(2000); } dht22AirTem = dht22AirTemSum / AveragingNumber; //23 if(dht22AirTem<10) //24 dht22Temperature = '0'; dht22Temperature = dht22Temperature + dht22AirTem; //25 dht22RelHum = dht22RelHumSum / AveragingNumber; if(dht22RelHum<10) dht22Humidity = '0'; dht22Humidity = dht22Humidity + dht22RelHum; }

4.2 The Code explained

In the following the different sections of the code are explained in more detail:

- The library DHT.h can also be used to communicate with the DHT-11, a smaller, less accurate, but faster module. It is necessary to give the type of DHT sensor when the object of class DHT is created (4). Defining the type at the top makes it easier to change between the different modules. Because in this case the DHT-22 is used, DHTTYPE is defined as DHT22.

- Here the GPIO pin used in the data-bus is chosen, also to make changing the pin easier and faster.

- To make the sketch the aforementioned library DHT.h must be installed and included.

- The object dht, representing the DHT-22 sensor, is created as an instance of the class DHT, provided by the library. During object creation, the GPIO pin (2) and the sensor type (1) must be given as arguments.

- Here the necessary variables are declared and initialized, for the temperature and humidity measurements, respectively. The first float variable (dht22AirTem & dht22RelHum) is used to take up the sensor values and later the final averaged value. The second float variable (dht22AirTemSum & dht22RelHumSum) are used to store the sum of the measurements which then is averaged over the number of measurements. The String object (dht22Temperature & dht22Humidity) are used later for printing the data and sending it with MQTT (not included in the sketch).

- If the power supply or the DHT-22 was disconnected due to the issues described in section 3.2.3, there is now some time to connect it again. This is only for the testing of the sensor.

- The Serial connection is started to check the sensor values using the serial monitor.

- The function measureDHTTemHum(), which is defined below (11), is executed. As an argument it expects the number of measurements which should be taken and averaged. A 1, will just give the result of 1 measurement. A 2 results in 2 measurements being taken, which are then summed up and divided by 2 to get the mean of the values. Increasing the number gives thus more accurate results (by reducing the influence of possible outliers due to measurement errors) but also increases the time necessary by a bit more than 2 seconds per additional measurement. In this case, 5 measurements are taken and averaged which means the function needs approximately 8 seconds.

- Here the values are plotted in the serial monitor. To plot the data, the string objects (5) are used.

- The delay of 2 seconds is included, because the function is just looping all the time. In the function, the 2 second break is only included until the final measurement is taken to save time in the real application later on, where the function is not looping almost continuously (22).

- The function measureDHTTemHum() is declared. This function is to be included in the real application later on. The function does not have any return value, it just actualizes the values stored in the variables declared in the beginning. As mentioned before, it expects a variable of the type byte (Averaging Number), which gives the number of measurements which should be taken.

- In the final application, the DHT-22 will not be supplied power continuously, but only when it is needed to measure. The rest of the time it will be shut down to save power as in stand-by mode there is still a 40 uA current if power is supplied. After supplying power to the DHT-22 VDD pin, the sensor is in an instable phase (section 3.2.1) which needs 1 second to pass, therefor the delay.

- The method begin() of the object dht declares the GPIO pin used as an input and activates the pullup, which is necessary for the communication between MCU and sensor that follows. It also resets a counter variable used in the library’s code.

- The value of the sum variables is reset to 0 and the string objects are emptied. The first float variable does not need to be reset, because it gets overwritten during each measurement anyways.

- The for-loop repeats the loop-body (the measurements) as many times as the number given as function argument (AveragingNumber).

- For the measurements, a do-while-loop is used, because it is necessary to measure at least once. It is possible that the measurements are erroneous, in that case, the measurement is repeated (21).

- The values for the float variables are overwritten by the current measurement results obtained by the readTemperature() and readHumidity() methods of the dht object.

- The function isnan() (IS Not A Number) gives back a 1 if the measurement was erroneous and did not yield a proper result. If the measurement was successful it returns a 0. In this if-statement the condition is defined as whether both (logical and - &&) of the measurements were successful. If both measurements were successful, isnan() returns a 0 for each of them; the 0 is turned to a 1 by the logical not (!) in front. Thus, if both measurements gave proper results, the condition is true.

- If that is the case the values obtained from the measurements (dht22AirTem & dht22RelHum) are added to the sum of the values.

- Otherwise, if the measurements were erroneous, there is a delay of 2 seconds, as a cool-down for the temperature sensor, so that another measurement can be taken.

- The while condition of the do-while-loop tests if any of the 2 measurements were erroneous. If that is the case, the loop starts again. If both the measurements were good, the loop is exited.

- This if control structure tests if the last measurement was taken already. If that is not the case, a delay of 2 seconds is done as a cool-down for the sensor, so another measurement can be taken afterwards. For example: if the averaging number is 3, and the third successful measurement was taken, i = 2 (because the increment happens after the execution of the statement of the for-loop). The averaging number minus 1 equals 2, which is not bigger than i. So, the delay of 2 seconds is omitted. i then gets incremented to 3, which does not fulfill the for-loop condition, so the loop is exited. During the final application, the sensor will be powered off again after executing the measurement function once, so it does not need a cool-down phase after the last measurement is done. To conclude, the if statement saves 2 seconds of time during the final project. In this code, the function loops constantly, therefore the 2 seconds delay in the main loop were necessary (10).

- Here the measurement readings are averaged by dividing their sum by the number of measurements.

- If the temperature drops below 10°C or the relative humidity below 10%, a leading 0 is added to the string objects. This way, the delivered string always has the same length which makes reading and transmitting the data later on easier.

- To the string object, the averaged measurement results are added. The string can then be used for printing to the serial monitor or for transmitting data through MQTT.

4.3 Results

As can be seen in the code (code section 1) a DHT-22 was used for testing and its data pin was connected to the GPIO pin 15 of the ESP32 DevkitC VB. As explained before, no additional pullup resistor was necessary.

After uploading, the code, the power supply to the DHT-22 was connected: 3.3V to VDD and GND to GND. After 5 seconds, the following was printed to the serial monitor:

15:54:35.854 -> Measurement is starting ... //1 15:54:35.854 -> Measuring ... //2 15:54:44.864 -> Temperature: 23.70 °C //3 15:54:44.864 -> Relative Humidity: 49.82 % //4 15:54:44.864 -> ============================== //5 15:54:46.904 -> Measuring ... //6 15:54:55.934 -> Temperature: 23.76 °C //7 15:54:55.934 -> Relative Humidity: 48.16 % //8 15:54:55.934 -> ============================== //9

Even though the resolution of the measurements is just 0.1 °C and 0.1 % RH (table 1), the values printed in the serial monitor have numbers other than 0 in the second decimal place; this is due to the values being averaged in the function. The measurements were taken in a living room, so temperature and humidity measurements yielded plausible results.

When observing the timestamps on the left, it is possible to see what was happening in the MCU. After the measurement began (line 2), the MCU needed another 9.01 seconds to print the results in the serial monitor (line 3, 4, 5).

- 1 second came from the delay (code section 12) to pass the unstable status.

- 8 seconds came from the delay (code section 22) as a cool-down for the thermistor.

- 0.01 seconds were necessary for the MCU to execute the remaining code

For 5 measurements being taken, the minimum delay time is 1 + 8 = 9 seconds. That means, that no improper results were obtained and the do-while loop was only executed once per execution of the for-loop statement.

Between the printing of the results (line 3, 4, 5) and the start of the next measurement process (line 6) a time difference of 2.04 seconds could be observed. 2 seconds are due to the delay in the main loop (code section 10), the rest is due to the print() functions which consume comparably much time.